Kouhei Fukushima

Kouhei Fukushima was born in 1995 in Fukuoka, Japan, and spent his childhood in Hiroshima.

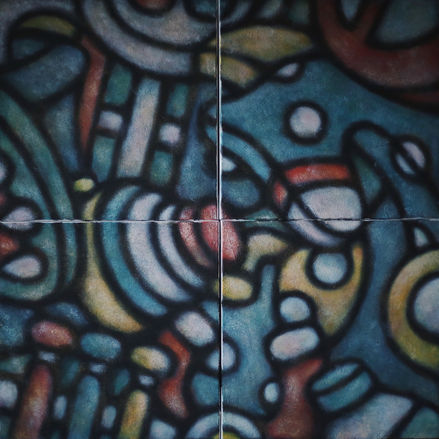

He observes society through his own filter, reconstructs it incorporates into his works with sensitivity. He always carries a spirit of resistance and the expression of his work continues to evolve.During his high school and university student, he majored in Architectural Environment, a background that inform the structural balance evident in his artwork.

In 2015, Fukushima embarked on a career as a professional BMX rider, showcasing his adventurous spirit and passion for dynamic forms of self-expression. By 2018, he shifted to artist.

Fukushima’s work is described as heterodox, blending a vast array of influences and sensibilities to continually innovate.

A vast amount of information and a universal sensibility. He is a painter who has uniquely updated those expressions.

PICK UP